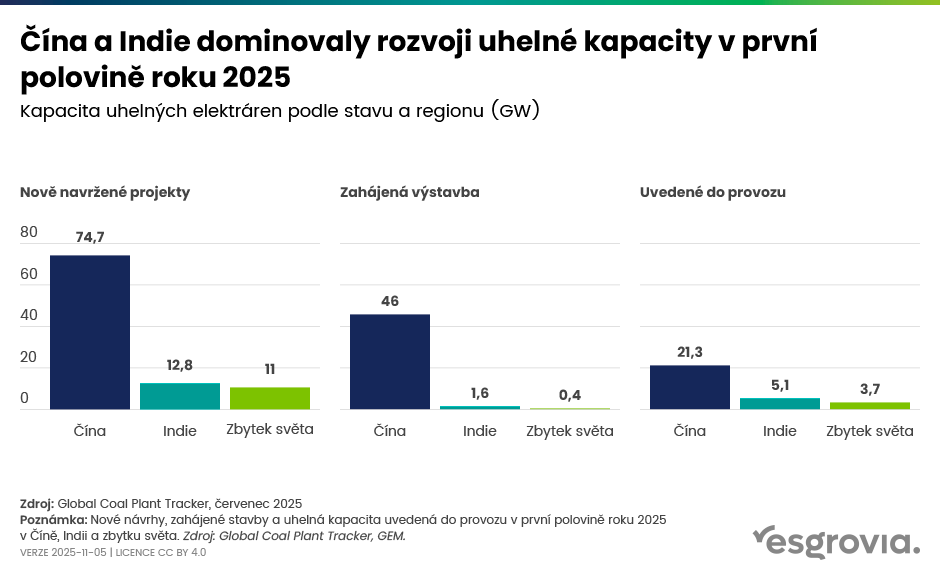

China and India account for 87% of new coal capacity in the first half of 2025

According to data from the Global Energy Monitor (GEM), China and India together represent 87% of newly added coal capacity for the first half of 2025.

While advanced economies are moving towards a gradual phase‑out of coal energy, China and India continue its expansion. This shows a growing global divide between those who are abandoning coal and those who continue to rely on it:

- China and India together commissioned, announced or started construction of coal power plants with a total capacity of roughly 87 GW (China ≈ 74.7 GW, India ≈ 12.8 GW), while the rest of the world added only about 11 GW.

- China launched or restarted construction of projects totalling 46 GW, keeping it on track to repeat the record year of 2024 (more than 97 GW of new projects).

- India commissioned about 5.1 GW of new coal capacity – more than the entire previous year 2024.

- In Europe and Latin America the construction of new coal power plants has almost halted; in Latin America there are currently no active proposals.

As Carbon Brief points out, for example, the Irish government in June 2025 shut down coal‑fired power plants and most EU countries plan to end coal generation by 2033.

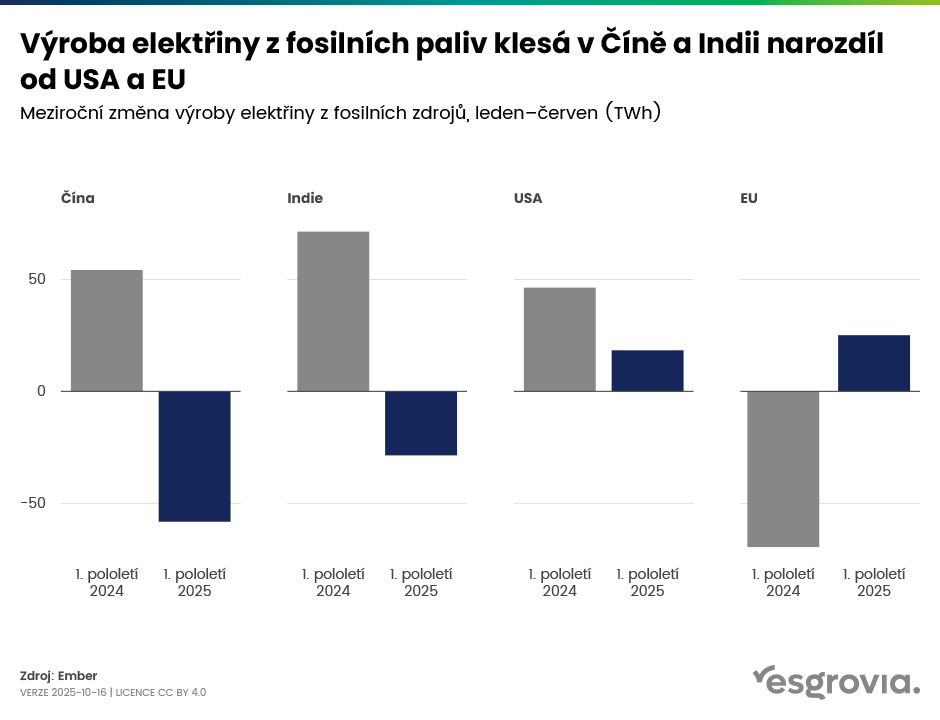

The figures for China and India are interesting in several other respects. First, the absolute production from fossil sources in China and India in the first half of 2025 fell, unlike in the US and the EU:

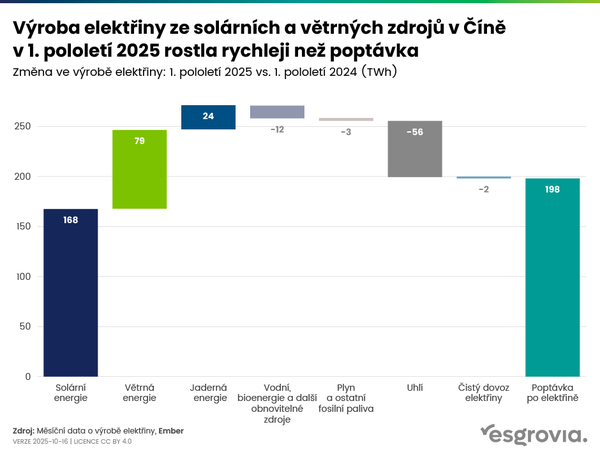

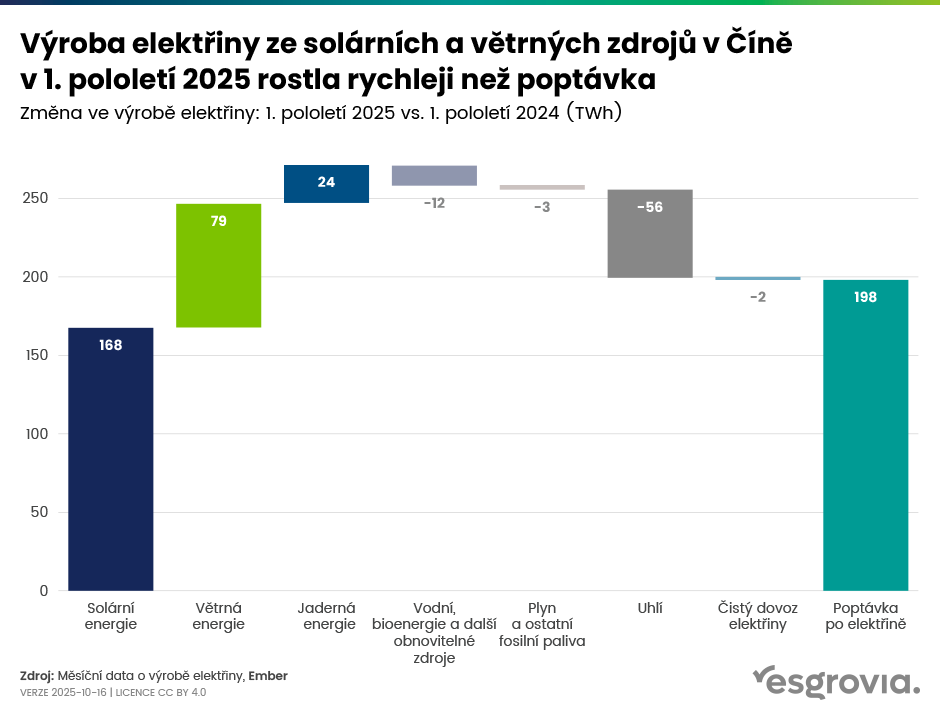

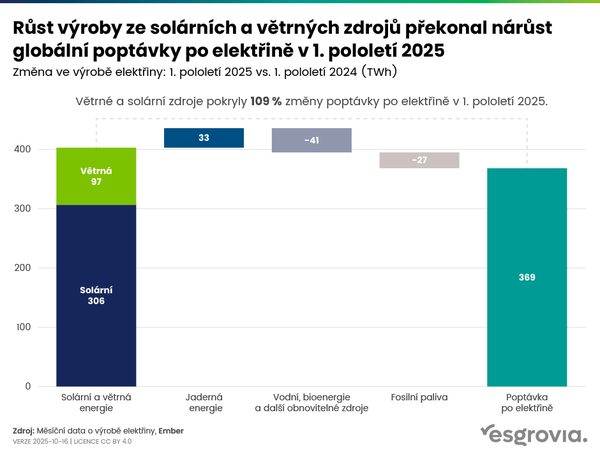

Secondly, the overall share of energy production from fossil sources in China and India is falling. In 2025 China increased the installation of solar and wind sources more than the rest of the world combined. Thus the growth of renewables outpaced the growth of its electricity demand and fossil‑fuel generation fell by 2%.

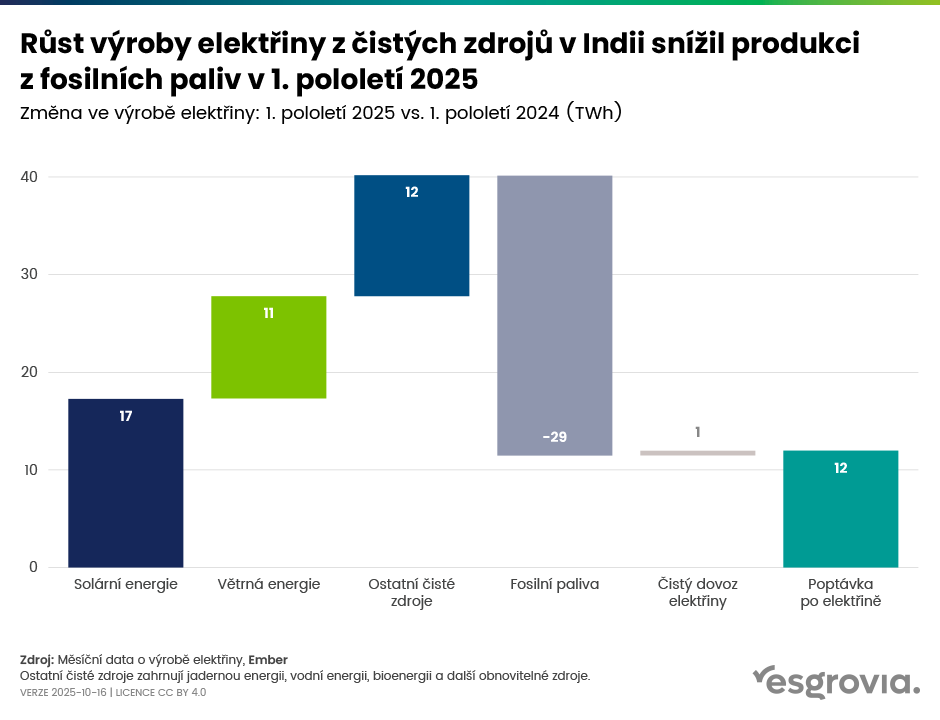

In India the situation is similar – it has also significantly boosted production from solar and wind energy and thereby reduced production from coal and gas:

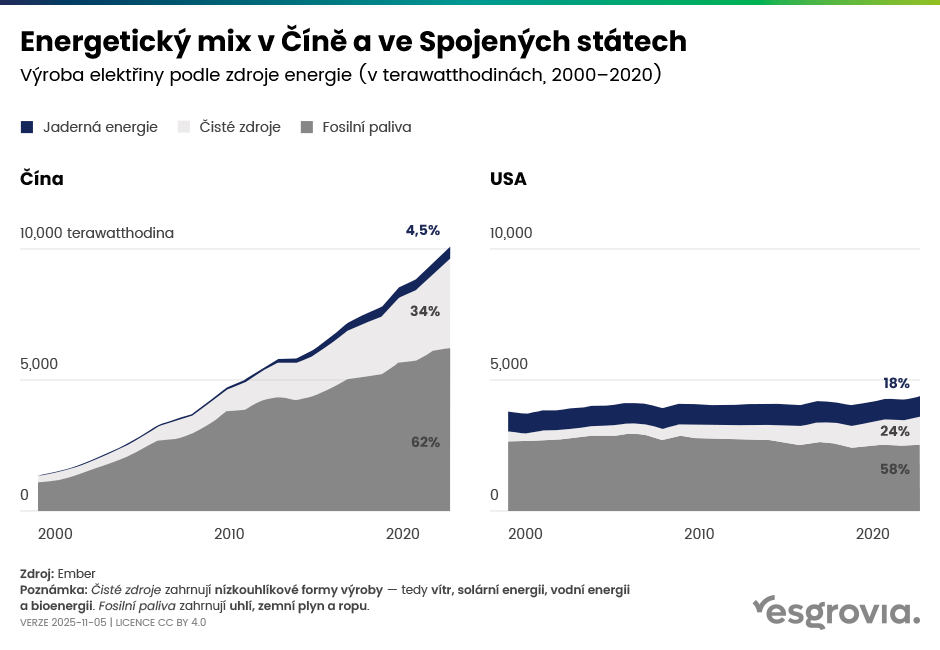

The problem therefore remains that both the Indian and Chinese governments simultaneously support further development of coal capacity. A coal peak in India, for example, is not expected before around 2040. While electricity generation and the share from renewables are rising, in large and fast‑growing countries this is not enough to meet the rapidly increasing energy demand of the economy, see the comparison of electricity generation between the USA and China:

Even though we see many positive examples of renewable growth and marked shifts in some regions (e.g., Europe, Latin America), the global picture remains very fragmented.

To achieve climate goals it is necessary to monitor not only the growth of renewables but also the slowdown and ultimately the halt of coal expansion. This is not yet happening in practice in these two key countries – China and India, where most new investments in coal energy take place.

The split between regions also intensifies inequalities – while some parts of the world are almost no longer investing in coal, other regions are significantly increasing capacity. This creates risks for global coordination of climate policy and for the balance between the economic needs of developing countries and climate goals and, consequently, for the competitiveness of individual countries and their businesses.

Related articles

Renewable sources overtook coal as the world's leading source of electricity for the first time

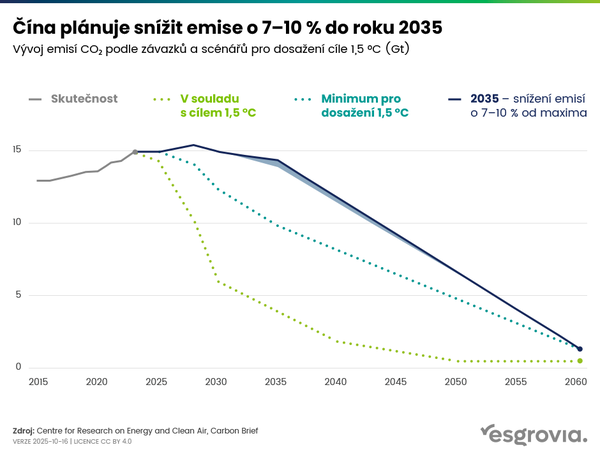

China plans to reduce emissions by 7–10% by 2035

Abundant cheap energy as a determining factor of business sustainability